Writing Maintainable Code with AI

Overview

You've heard the complaints: AI code is bloated, slow, and unmaintainable. Supporters say "You're using it wrong!". Skeptics retort, "If it's so smart, why doesn't it just write good code?" Both sides have a point. AI can be good at generating code, but it falls short of the advertised PhD-level intelligence.

As a former skeptic turned proponent, vague advice like "use it right" isn't enough. In this post, I'll show you a technique for generating working, maintainable code.

Doing it Wrong

Sometimes it's good to see how to do things wrong so we can appreciate how to do it right. Let's walk through a bad prompt to see why it's bad:

Write an application to pick colors.

This prompt is just terrible. These models are trained on hundreds of billions of data points and they'll just string a few of those data points together that are remotely connected to color pickers. Here's just a small sample of things that could be specified in the prompt, but were omitted (making it a "bad" prompt):

- What programming language to use?

- How should the application function?

- How to pick colors?

- What operating system should this run on?

- What should the interface look like?

- Should there even be an interface?

- Should it do more than just pick colors?

Failing to specify these parameters hands control over to the model to come up with solutions. So if you cared about any of those things, then this prompt would fail because it's going to pick whatever it was trained the most on.

Here’s the results of trying that prompt with models of varying capabilities:

| Model | Language | Log | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

glm-4.7 |

Python, HTML/JS | link | ✅ Works |

grok-4.1-fast |

HTML/JS | link | ✅ Works |

trinity-mini |

Python, HTML | link | ❌ Mostly broken |

gpt-oss-120b |

Python, HTML/JS | link | ✅ Works |

llama-3.1-8b-instruct |

HTML/JS | link | ❌ Completely broken |

claude-opus-4.5 |

HTML/JS | link | ✅ Works |

Doing it Wrong-ish

Some of the color pickers are impressive, others not so much. However, the biggest problem here is that none of them generated anything remotely close to what I actually wanted. If I take a moment to elucidate on what my idea of a color picker should be, I can come up with this detailed prompt:

Create a program that, when a keyboard shortcut is pressed, activates a "color picker" mode which allows me to click on any pixel on the screen to query its color. There should be a small floating preview that follows the cursor. This preview should be zoomed in so the user can see which pixel is directly under the cursor. Pressing ESC exits the "color picker" mode.

After clicking on the screen, this should happen:

- The hex value of the color should be copied to the clipboard.

- A small window should appear containing a color selection wheel, an input box for hex colors, a "copy color" button, two color preview squares, and a "pick" button which closes the window and goes back into "color picker" mode.

- The initial value for the color wheel and input hex code should be set to the picked screen color.

- The color wheel and hex color input box should be synced.

- One color preview square should be the picked screen color and remain static, the other preview square should be the wheel/input box color.

- Pressing the ESC key closes the window.

This only needs to work on Linux+Wayland. I'm using KDE Plasma.

This prompt feels better because it provides multiple specifications and describes the behavior in more precise detail. The model doesn't have to guess what "click on the screen" means because it's listed right there in the prompt. UX transitions are documented: what happens when ESC is pressed, what happens when a pixel is clicked, what happens when the "pick" button is pressed. There is still some ambiguity, but properly written coding agents should be able to help disambiguate this and other issues before they start generating code.

Given all the detail provided, it feels like we may actually get a good result! I used glm-4.7 via a coding agent which generated a plan. It also asked a few questions about what libraries I wanted to use, how to capture screenshots, and how to handle keyboard shortcuts. I answered the questions and it went ahead and did its agent loop which resulted in:

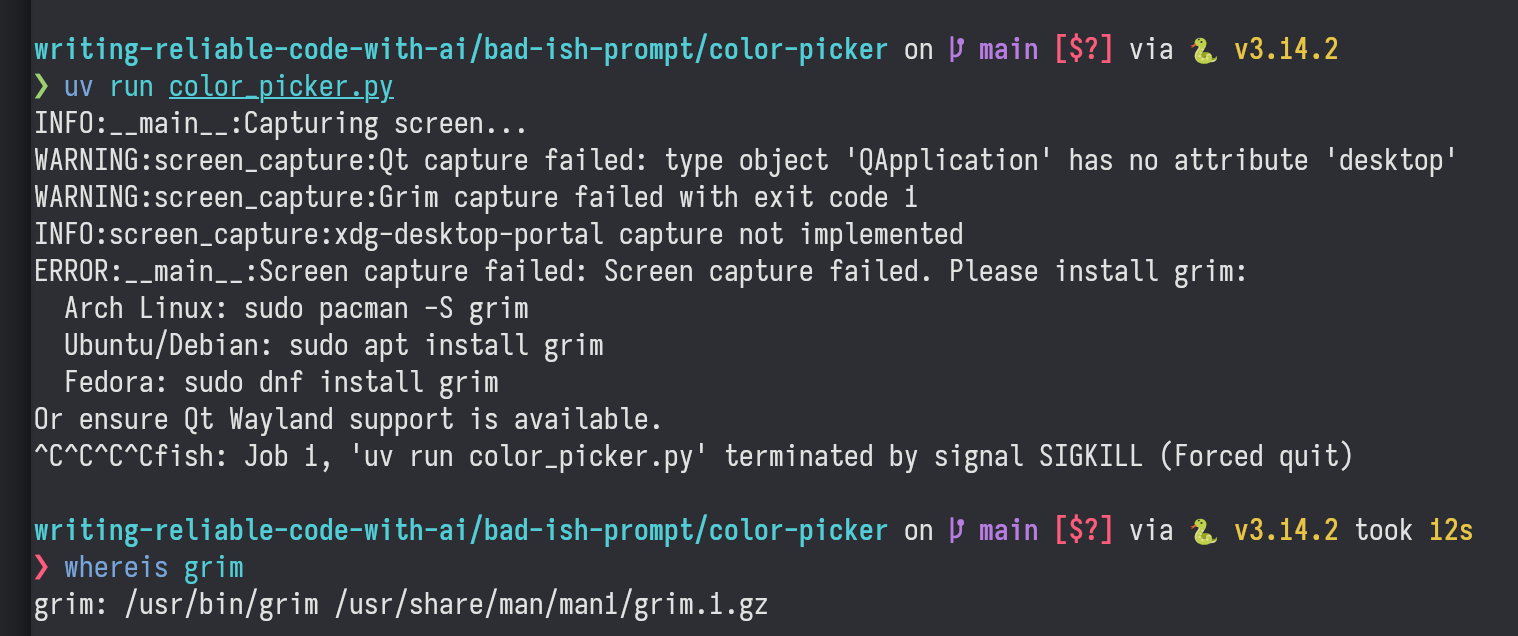

A non-functioning program!

Now it's possible that there's just a small error somewhere, and that fixing it would make the program work. But I'm not going to do that because, even without looking at the code, I already know it's poor quality. If you take a look at the screenshot, you'll see a bunch of ^C followed by a termination message. That's me trying to kill the program with ctrl-c, followed by a kill -9. Additionally, it couldn't find the grim binary for taking screenshots even though the agent listed it as one of the choices for screenshot functionality, which I picked because I already had it installed. These are basic things that aren't even related to the primary functionality of the program.

The prompt did provide much more detail, and the act of writing it implicitly forced me to think through exactly what I wanted, which is great. But the fact is that giving more instructions using plain-English is not a viable solution to generate working software, let alone working software with high code quality. In fact, more instructions actually degraded the output to the point that it doesn't work at all. At least some of the working pickers from the previous section hooked into the desktop's/UI frameworks color picker, which does have a "pick screen color" option. We need a better approach.

You're Smart, LLMs Are Dumb

The current generation of models are fancy auto-completion engines with really good pattern atchingcapabilities. There are even APIs specifically called "Chat Completions" with the word completion in the URL. If we internalize the fact that LLMs are auto-completion engines, then we will be better equipped to leverage their capabilities.

Since they are completing the input, if you start off with only a brief description of what you want, then they are just going to complete it using whatever they were trained on. This will almost always be code of varying (and probably poor) quality. Imagine how many data points are out there of example code and tutorial code that purposefully omit all the complexities of maintainable code. And then imagine all the GitHub repos that include simple tools that do actually work, but were never meant to be used for production systems, like the 270k dotfiles repos. The models are fully equipped to generate unmaintainable code. However, if you start with high-quality code as the input, then the model actually can complete it with high-quality output. They are really good at following patterns, but you need to guide the models by showing them what high-quality code looks like first.

This introduces a problem: If we need to provide high-quality code for a model to complete, isn't that just us writing the code? Yes and no:

- Yes, you need to provide some high-quality code.

- No, you don't need to write the majority of it. And the more you know about good programming practices, the less you need to write.

Models are trained on everything, including existing high-quality code patterns and software development methodologies. But you also need to know about the patterns and software development methodologies in order to use them with a LLM. Remember, the model completes inputs, so you'll need to use your human brain to get the input to a high-quality state first. In your prompt you'll need to invoke terminology that's used by practitioners and documented in the methodologies. This will theoretically cause specific activations in the model which are more closely related to high-quality training data, which then lead to better code generation.

Here's a very abbreviated list of knowledge you can leverage to help generate better code:

- Test-Driven Development (TDD)

- Behavior-Driven Development (BDD)

- Domain-Driven Design (DDD)

- SOLID principles

- Well-established design patterns

I'm going to reference concepts from few of these throughout this post and I'll provide a brief description of how they work prior to using it. This way you don't need to become an expert to start applying these concepts right away. But I do highly recommend becoming familiar with these techniques as it will help improve your code overall.

Planting The Seed

We're going to switch gears from generating an application to generating just a single module of an application. Why? Because that's the only way to generate high-quality code using LLMs. We need to write a little bit of code to get the process started, and then the model will be able to replicate the coding standards elsewhere.

Many applications need to save data to disk, so we'll create a persistence module using the Repository Pattern.

The Repository Pattern adds an abstraction layer over persistence. Instead of accessing a database directly, you'll access the

repository. This layer of abstraction allows us to swap out the database for an in-memory structure.For example, if you wanted to get a list of all users, instead of

db.query("SELECT * FROM user"), you'd writerepository.list_all_users().

Coding agents and LLMs won't automatically implement this pattern unless asked to. Even then, it's better to show them what we want rather than telling them and hoping for the best. Below is some code that sets up the Repository Pattern. I've only included the trait here since that's the important bit, but if you are interested you can check out the complete source code here:

use async_trait::async_trait;

use error_stack::Report;

/// Implemented on backends for data persistence.

#[async_trait]

pub trait UserRepository {

/// Returns a user.

///

/// # Errors

///

/// Returns an `Err` if the backend encounters a problem while reading.

async fn get_user(&self, user: Id<User>) -> Result<Option<User>, Report<UserRepositoryError>>;

/// Returns all users.

///

/// # Errors

///

/// Returns an `Err` if the backend encounters a problem while reading.

async fn get_all_users(&self)

-> Result<Vec<User>, Report<UserRepositoryError>>;

/// Inserts a new user, overwriting an existing user with the same [`UserId`].

///

/// # Errors

///

/// Returns an `Err` if the backend encounters a problem while writing.

async fn insert_user(&self, user: User) -> Result<(), Report<UserRepositoryError>>;

/// Removes a user, returning `Some(User)` if the user was removed successfully.

///

/// # Errors

///

/// Returns an `Err` if the backend encounters a problem while writing.

async fn remove_user(

&self,

user: Id<User>,

) -> Result<Option<User>, Report<UserRepositoryError>>;

}

Why didn't I just describe exactly what I wanted in a prompt and then have the model generate the code? Even though I know it won't work, I tried it anyway, six times:

| Attempt | Issues |

|---|---|

| Gen 1 | Wasn't async, didn't use Result, wrote more stuff like a fn main, IDs were u32. |

| Gen 2 | Used Result, manual implementation of Error, didn't use async_trait. |

| Gen 3 | Actually decent, but then it added an associated type which breaks object safety. The point of the repository pattern is that we can swap out the backend. If we can't make a trait object then it makes the code harder to work with and limits us to a single backend picked at compile time. |

| Gen 4 | Back to object-safe trait, but now the Result type has an alias that I didn't ask for. |

| Gen 5 | I told it to use the error_stack crate for errors and to write documentation similar to stdlib. It didn't use error_stack correctly, and the generated examples in the documentation didn't compile. |

| Gen 6 | It used an enum for the error type, even though I told it to use a struct. I also told it to not use examples in the docs, so it replaced them with # Returns sections instead, which isn't how the stdlib documentation is written. I gave this one a second turn since it was pretty close and asked it to use a struct for the error type. After an unreasonable amount of thinking for such a small change, it wrote an error struct with message and source fields, completely unaware that the error_stack crate handles all of that and it should just be a unit struct. |

It's funny looking back at the session snapshots and seeing the prompt slowly grow in size with each generation in my futile attempt to try and steer the model to the desired code. And keep in mind, all of this prompting was just to generate the method signatures for a single trait. This isn't even for code that actually does anything!

So we know that the model isn't capable of generating maintainable code on its own, and that's why I hand-wrote the code. Hand-writing the initial "seed" is like providing precise instructions in the form of code. Models fail quickly when you try and complete some English instructions because they first need to find something matching those English instructions, and then attempt to complete whatever comes after them. But most code is followed by more code, and the only time plain English is followed by code is in code comments and blog posts. Instead, if we use code as instructions then we leverage the strength of completion models: they can complete the given code (instructions) easily because in the training data code is followed by more code.

This is why it's important to have a good understanding of the principles and techniques which result in high-quality code. If we are using code as instructions (or as a template), then that code needs to be good. Otherwise, the model will copy the bad code and generate more bad code. It's the ultimate garbage in, garbage out machine.

Generating Test Code From an Interface

To get started, we will have the model generate a Fake repository.

A "fake" is test double that implements the interface and provides the expected functionality. It typically operates on in-memory data structures, making it great for testing but unsuitable for production workloads.

Since the "fake" actually works, it will allow us to call insert_user and then later actually get that user back using get_user.

We'll give the entire file to the model and tell it to implement a fake. No special prompting tricks are needed here and you don't have to worry about listing out a bunch of conditions/constraints/instructions:

Generate a fake test double for

UserRepository.

Why such a simple prompt? The code itself acts as detailed instructions (or blueprint) for the model. And the code comments explain what should happen for each method. This means that we've already provided the instructions, they are just in the form of code.

We can imagine that model completion works like this:

- Read the input text, one token at a time. For example, "The sky is ".

- Encounter "Assistant's turn" token.

- It completes the sentence: "blue".

There's no guarantee that a model completes exactly what you expect. Here's a few example completions for "The sky is ":

- "...blue. Or is it? The color of the sky can vary depending on the time of day, weather conditions, and atmospheric phenomena. It can be a bright blue, a deep gray, a fiery orange, or even a vibrant purple! What's your favorite color of the sky?"

- "blue (on a clear day, thanks to Rayleigh scattering of sunlight by Earth's atmosphere). What's next? 😊"

- " ...blue. ...cloudy. ...clear. ...gray. ...dark. ...filled with stars. ...a canvas of colors during sunset."

Applying this to code, a completion looks like this:

- Read the existing code, one token at a time.

- See "Generate a fake test double for

UserRepository" immediately after the code. - Encounter "Assistant's turn" token.

- It completes the input and hopefully generates the right code.

If there's nothing in the training data for our specific code, then we may be out of luck. However, if we keep our completions small in scale, then we increase our chances of landing on something relevant. We've already massively reduced the amount of work for the model since it only needs to complete the method bodies, and we've leaned into its main strength: completing existing text.

Here's the code returned by the model for "Generate a fake test double for UserRepository":

use std::collections::HashMap;;

use async_trait::async_trait;

use error_stack::Report;

use tokio::sync::RwLock;

/// A fake in-memory implementation of [`UserRepository`] for testing.

///

/// Stores all users in an in-memory `RwLock<HashMap>`.

#[derive(Debug, Default)]

pub struct FakeUserRepository {

users: RwLock<HashMap<Id<User>, User>>,

}

#[async_trait]

impl UserRepository for FakeUserRepository {

async fn get_user(&self, user: Id<User>) -> Result<Option<User>, Report<UserRepositoryError>> {

let users = self.users.read().await;

Ok(users.get(&user).cloned())

}

async fn get_all_users(&self) -> Result<Vec<User>, Report<UserRepositoryError>> {

let users = self.users.read().await;

Ok(users.values().cloned().collect())

}

async fn insert_user(&self, user: User) -> Result<(), Report<UserRepositoryError>> {

let mut users = self.users.write().await;

users.insert(user.id, user);

Ok(())

}

async fn remove_user(

&self,

user: Id<User>,

) -> Result<Option<User>, Report<UserRepositoryError>> {

let mut users = self.users.write().await;

Ok(users.remove(&user))

}

}

Note that I used x-ai/grok-4.1-fast to generate this completion using the default OpenRouter system prompt. There's no special coding prompts, no coding-specific models, no agent loops, and I'm sending a standalone LLM request.

Pro tip: The best techniques involve splitting the work up into the smallest chunks possible, enabling you to use cheaper models. This specific prompt also works with

amazon/nova-lite-v1,arcee-ai/trinity-mini,qwen/qwen3-30b-a3b-thinking-2507, andmeta-llama/llama-3.3-70b-instruct.

So far so good. Now we need tests for the FakeUserRepository. If you aren't too familiar with TDD, then writing tests for something only used for testing might seem kind of crazy. But there are some good reasons to do this:

- The fake needs to work correctly when testing other parts of the system that use the fake.

- The tests are going to be re-used for all future implementations of this trait, so we need the tests regardless.

- We can use the fake to discover potential shortcomings with the API provided by the trait. Like maybe the API design is too verbose or prone to incorrect usage. This would be revealed in the test code.

Don't worry, I did say we "need tests", not that we'll be writing them!

Let's defer test generation to the LLM by prompting it to generate a list of potential tests:

Given the following code, please generate a list of test names for the

UserRepository. Only include test names. Use BDD-style naming conventions (ie: gets_user, returns_none_when_getting_non_existent_user).

After we get the test list back, we can then generate the actual test code:

Generate tests for

FakeUserRepositoryfollowing BDD practices. Test methods should focus on one thing only with a minimal (1-2) number of assertions and follow this form:#[rstest] #[case::fake_user_repo(FakeUserRepository::new())] #[tokio::test] async fn name_of_the_test(#[case] repo: impl UserRepository) { // Given (describe initial conditions) (setup code here) // When (describe the action taken) (action code here) // Then (describe the expected result) (assertion here) }Here is the list of tests to generate for the

FakeUserRepository:

- returns_none_when_getting_non_existent_user

- returns_user_when_getting_existing_user

- returns_inserted_user_when_getting_by_id

- returns_empty_vec_when_getting_all_users_with_no_users

- returns_all_users_when_getting_all_users

- returns_all_inserted_users_when_getting_all_users

- successfully_inserts_new_user

- overwrites_existing_user_when_inserting_same_id

- successfully_inserts_multiple_users

- returns_removed_user_when_removing_existing_user

- returns_none_when_removing_non_existent_user

- returns_none_from_get_user_after_removing_user

- get_all_users_excludes_removed_user_after_remove

- get_all_users_includes_newly_inserted_user

- get_all_users_excludes_overwritten_user_after_insert

Note that a little more specificity is required this time around. I provided an example of how we want the tests to look, followed by each test to generate. I used #[rstest] to parameterize the tests so they can be re-used later for other implementations.

Providing a long list of things to do as a single prompt to a model generally doesn't scale down to smaller/cheaper models. While it is possible to make it work with smaller models, it requires a capable agent to split it up properly. For the purposes of this demonstration I'm keeping this as a 1-shot prompt to show that the technique works.

To try and mitigate the chances of the LLM missing a test case, I switched to the slightly more expensive x-ai/grok-code-fast-1. For full transparency: the entirety of the context so far is the code that we've generated and the prompt above, which includes the list of generated test names. There's no massive web of rules nor prompt files or anything like that. Just what you've seen so far in this post with the default "you are an assistant" system prompt provided by OpenRouter.

After sending off the prompt, the model returns a bunch of test code that looks like this:

#[rstest]

#[case::fake_user_repo(FakeUserRepository::default())]

#[tokio::test]

async fn successfully_inserts_new_user(#[case] repo: impl UserRepository) {

// Given: A repository (initially empty)

// When: Inserting a new user

let user = User {

id: Id::<User>::default(),

name: "Grace".to_string(),

};

let insert_result = repo.insert_user(user.clone()).await;

// Then: It should succeed (insert_result is Ok(()))

assert!(insert_result.is_ok());

}

Now we are the proud owners of a tested, working, in-memory repository! That's great for testing other parts of the program, but we can't actually use this because we want the application to save and load stuff while interacting with the disk, not just mess around in memory. But now we can leverage this fake to generate some more code.

Generating a Real Implementation

Remember when I mentioned that we can treat the code as high-quality instructions for the model? We are going to take all the code written so far and use that to write a real implementation. We'll use NDJSON for our file format because it's something that the model can probably implement in 1 shot and I'm trying to avoid firing up an agent loop.

We've built up some code starting with a manually-written trait, then generated a fake implementation, followed by some generated test cases. All of this has been a process of encoding instructions for the model in the form of program code. The model will see all of our "instructions" in the context and then generate a completion based on that input. To get a working NDJSON implementation, we just need load up the code into the context window and act as a director:

Using the existing code as a guide, write an implementation of

UserRepositorythat uses NDJSON for persistence. Only write the implementation, no tests.

Here's the result, 1 LLM call, no coding system prompt, x-ai/grok-4.1-fast:

use std::collections::HashMap;

use std::io::ErrorKind;

use std::path::PathBuf;

use async_trait::async_trait;

use error_stack::{Report, ResultExt};

use tokio::sync::RwLock;

use crate::repo::{Id, User, UserRepository, UserRepositoryError};

use serde_json;

use tokio::fs::{create_dir_all, read_to_string, write};

#[derive(Debug)]

pub struct NDJsonUserRepository {

path: PathBuf,

users: RwLock<HashMap<Id<User>, User>>,

}

impl NDJsonUserRepository {

/// Creates a new repository loading users from the NDJSON file at the given path.

pub async fn new(path: impl Into<PathBuf>) -> Result<Self, Report<UserRepositoryError>> {

let path = path.into();

let mut users_map = HashMap::new();

let content = match read_to_string(&path).await {

Ok(content) => content,

Err(e) if e.kind() == ErrorKind::NotFound => String::new(),

Err(e) => {

return Err(Report::from(e).change_context(UserRepositoryError));

}

};

for line in content.lines() {

let line = line.trim();

if line.is_empty() {

continue;

}

let user: User = serde_json::from_str(line).change_context(UserRepositoryError)?;

users_map.insert(user.id, user);

}

Ok(Self {

path,

users: RwLock::new(users_map),

})

}

async fn save(&self) -> Result<(), Report<UserRepositoryError>> {

let users = self.users.read().await;

let mut lines = Vec::with_capacity(users.len());

for user in users.values() {

lines.push(serde_json::to_string(user).change_context(UserRepositoryError)?);

}

let content = lines.join("\n");

if let Some(parent) = self.path.parent() {

create_dir_all(parent)

.await

.change_context(UserRepositoryError)?;

}

write(&self.path, content)

.await

.change_context(UserRepositoryError)?;

Ok(())

}

}

#[async_trait]

impl UserRepository for NDJsonUserRepository {

async fn get_user(&self, user: Id<User>) -> Result<Option<User>, Report<UserRepositoryError>> {

let users = self.users.read().await;

Ok(users.get(&user).cloned())

}

async fn get_all_users(&self) -> Result<Vec<User>, Report<UserRepositoryError>> {

let users = self.users.read().await;

Ok(users.values().cloned().collect())

}

async fn insert_user(&self, user: User) -> Result<(), Report<UserRepositoryError>> {

{

let mut users = self.users.write().await;

users.insert(user.id, user);

}

self.save().await

}

async fn remove_user(

&self,

user: Id<User>,

) -> Result<Option<User>, Report<UserRepositoryError>> {

let prev = {

let mut users = self.users.write().await;

users.remove(&user)

};

self.save().await?;

Ok(prev)

}

}

The generated code even caches the users in memory so read requests don't hit the disk, which is pretty nice. It copied the signatures correctly and also maps the errors to the expected type. It saw that we are using async and so it imported tokio and used the async versions of file access.

Before we accept this code, we need to confirm that this implementation actually works by adding a new case to all of the tests. You can use the LLM to do this, or take about 5 second spamming n. in Neovim. I also wrote a small helper to create a new NDJsonUserRespository because it's too verbose to construct for each case:

use tempfile::NamedTempFile;

async fn empty_ndjson_repo() -> NDJsonUserRepository {

NDJsonUserRepository::new(NamedTempFile::new().unwrap().path().to_path_buf())

.await

.unwrap()

}

#[rstest]

#[case::fake_user_repo(FakeUserRepository::new())]

// newly added

#[case::ndjson_user_repo(empty_ndjson_repo().await)]

#[tokio::test]

async fn returns_none_when_getting_non_existent_user(#[case] repo: impl UserRepository) {

// (test code omitted)

}

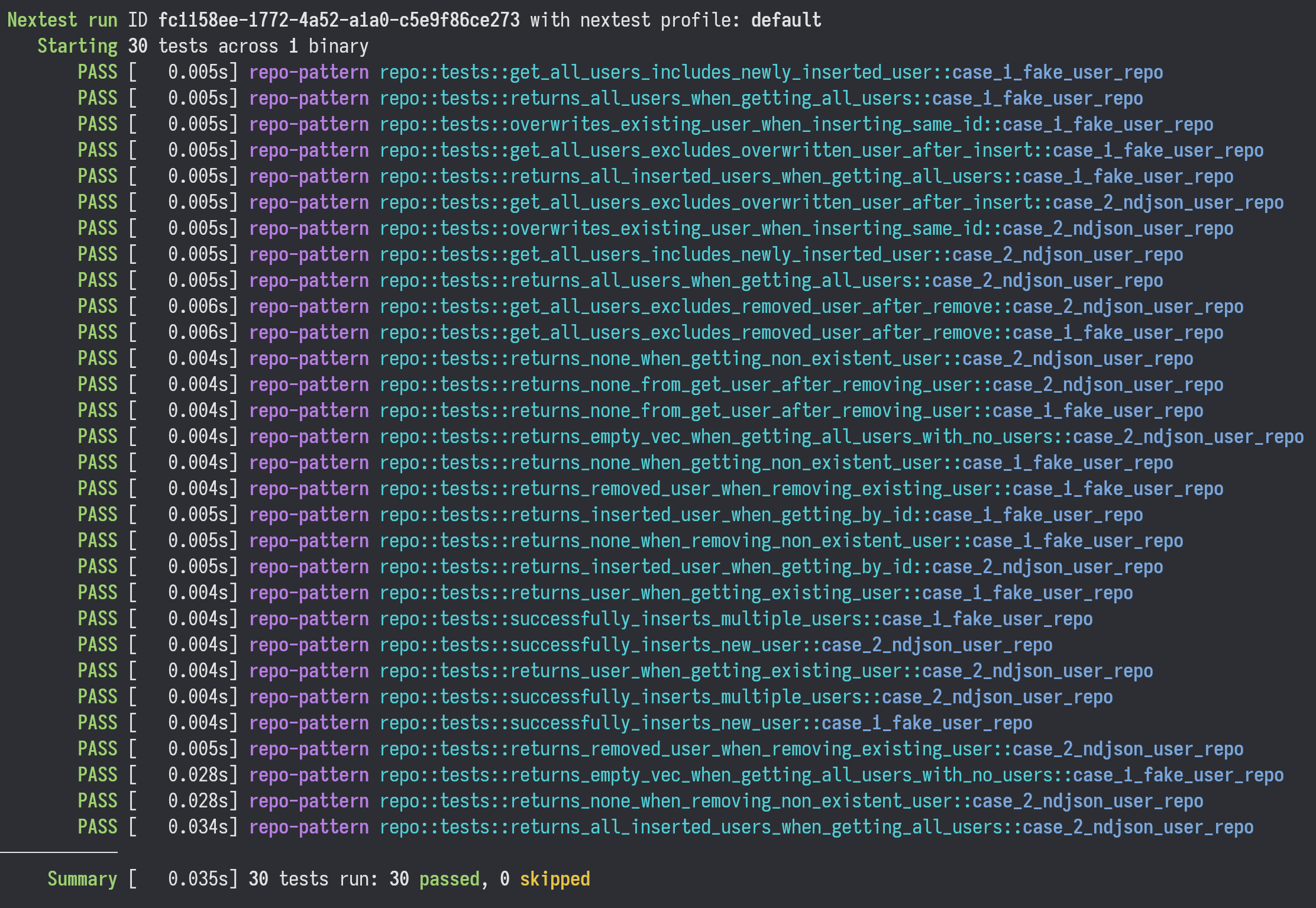

After running the test suite, all the tests pass for the new implementation:

Recap

I covered a lot in this post, so let's briefly go over the steps:

- Learn some techniques like BDD or TDD to broaden your knowledge.

- The model already knows the jargon, so you can save a lot of time by learning it too. Saying "Create a facade for this" is much quicker than trying to describe what to do.

- Create an interface/trait and include code comments that describe how the interface is supposed to work.

- Maintainable code is going to have comments on all of the interfaces anyway, so this is something that needs to get done regardless.

- Writing comments helps you think about the implications of using the interface. It's not as good as using TDD, but it's better than nothing.

- Generate a fake test double that implements the interface/trait.

- Models should be able to 1-shot this for many cases. If you are using an agent and it can't generate the fake, then your interface is probably too complicated. Mitigations include reducing the amount of methods in the trait and adding more types that handle complexity elsewhere (like

AdminandUsertypes so you don't need to check theaccount_typein the trait).

- Models should be able to 1-shot this for many cases. If you are using an agent and it can't generate the fake, then your interface is probably too complicated. Mitigations include reducing the amount of methods in the trait and adding more types that handle complexity elsewhere (like

- Generate a list of potential test cases.

- Review them since they might contain something you didn't think of. There might also be duplicates.

- In my initial trait, I had a copy+paste bug where the

get_all_userstookuser: UserIdas a parameter. Reviewing the test list and seeingget_all_users_returns_all_users_regardless_of_idtipped me off that I made a mistake in the interface. - Don't specify the number of cases to make. This will just make the model hallucinate stuff to meet the quota.

- Generate the tests using the list.

- Provide an example of how you want the tests to look. This is mandatory because there's a huge amount of bad test code out there, and just saying "Use BDD/TDD" isn't enough.

- Remember: running a completion from an example means the model will complete it in that same format, not whatever it pulls out of the training data. You should almost always show or tell the model what kind of output you expect for all requests, not just code.

- Run the tests to confirm that the fake implementation works.

- If it fails, then feed the error messages back into the model. An agent will do this automatically.

- After all tests pass, you now have a working reference implementation that you can use for integration tests.

- Generate the real implementation by telling the model to use the reference implementation as a guide.

Tips

You only need to do all the steps once or twice for each major section in any given codebase. Once you have a source of high-quality maintainable code, you can tell the model to go look at that code as a reference (assuming you are using an agent with filesystem access). Some examples:

Implement tests using a format similar to the tests in

src/my_awesome_thing.rs. Here is a list of tests to implement: (list your tests here)

Write a Cucumber test for (feature).rs

. Seetest/features/my_e2e_test.rs` for details on how to set up the test runner.

You could also add a skill/rule file that describes how you want the tests to look. I have one for BDD Given/When/Then style tests. But most of the time I prefer directing the model to use an existing source file because each project will be a little bit different. Using existing code means it will adhere to the coding standards set for that particular project.

Conclusion

The workflow I've demonstrated replaces guesswork with a structured process that plays to a large language model's strengths. By writing a well-designed interface by hand, generating the simplest possible implementation first, building up a comprehensive test suite, and then expanding to more complex implementations, you sidestep the biggest problem with LLM-assisted coding: lack of specificity.

This way you're not fighting against a model trying to guess your intent. The code provides a clear blueprint and you let the model fill in the blanks. The interface is your specification and the tests are your acceptance criteria. The fake implementation is your working reference, and the real implementation is just the next logical completion in that sequence.

This approach scales. You start with an interface and a fake, then you add more implementations as needed. The tests verify behavior consistency across all of them. You can swap implementations at runtime, you can add logging, caching, metrics, or completely different backends without modifying code that depends on the trait. Now that LLMs can generate most of the code, it's justifiable to spend more time up-front to design good interfaces.

I wrote this post because AI-written code doesn't have to be an unmaintainable, low-quality mess. In fact, properly leveraging AI has the potential to increase overall code quality, provided that you have the knowledge to do so. I'm hoping that my post helped to increase your understanding of how LLMs can be used for code generation.

Comments